Almost every teen has a phone, yet schools across the U.S. and abroad now move from loose rules to tight...

Digital Distractions: How Many Students Get Distracted by Phones in Class

Classrooms feel full of cell phones. The loud claim – that phones are a distraction in school – raises a fair question: how many students drift off-task in class. This research seeks a clear count based on fresh surveys and large studies, rather than hunches. Numbers show how cell phone use breaks focus, sparks side chats, and nudges eyes from the board. By the end, you get an answer on scale and impact – and what the evidence says about student learning.

Table of Content

ToggleWhat Counts as “Distraction”?

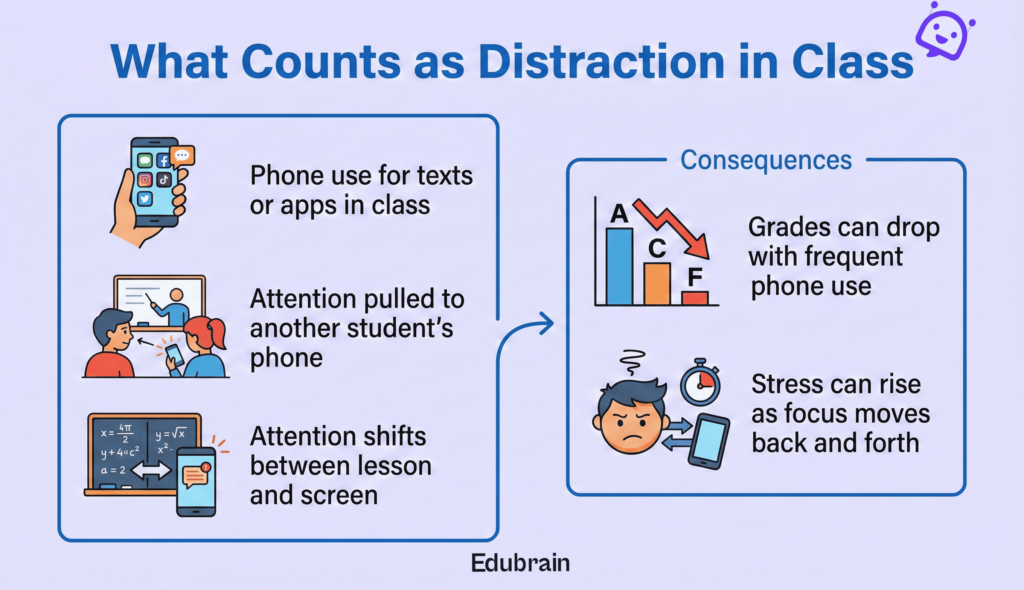

Distraction covers off-task cell phone usage (texts, social apps, quick games) and “peer distraction,” where nearby mobile phones or other digital devices steal attention. The device can sit face-down and still pull focus. Researchers compare student self-reports, teacher logs, and app records; results vary across K-12 and college students, and they change under bans with weak enforcement. Studies link off-task use to lower academic performance and added strain on students mental health. Good rules also enable students to use tech with purpose: tools in communication education and coding homework help resources sit beside calculators and note apps, so phones support the task rather than derail it.

Snapshot: The Latest Top-Line Numbers

Concern sits high among high school teachers: 72% call phone use a major distraction in the classroom, while across K-12, about one-third say “major problem” and nearly a quarter say “minor problem.” During a typical school day, student self-reports from PISA 2022 indicate frequent checks, even in areas where bans are in place, and a strong peer-distraction effect.

- 72% of U.S. high school teachers say cell phones are a major classroom problem.

- In schools with bans, 29% still use smartphones several times a day; 21% report daily or almost-daily use at school.

- 59% say peers’ digital devices divert attention in at least some maths lessons.

- By the end of 2024, 79 education systems (≈approximately 40% worldwide) had policies limiting the use of phones during school hours.

These figures frame practical questions for educational psychology and digital literacy. Policies spread quickly, yet enforcement varies; habits persist without clear routines that teach students self-discipline. Round-ups from Common Sense Media also highlight broad concern among educators and families, underscoring the need to teach students boundaries that are effective throughout the entire school day.

K-12 vs Higher Education

A phone, which is being used by a student sitting two seats away, causes a spillover, so even the students who try to focus are distracted by phones in the classroom. PISA data also indicates that in schools with bans, checking during the class is considered by teachers as rule-evasion. This pattern correlates with a negative impact on math results. The picture changes outside the school yard. College cohorts talk of self-directed multitasking (quick texts, socials, email) and then concede that they have lost time and weakened recall. This separation is important for the policy. Many schools are strengthening their measures by establishing clear rules and visible enforcement. Universities, through design choices, participation marks, and tech-on/tech-off cues that are in harmony with the lesson, facilitate responsible use.

| Setting | What happens | Effect |

| K–12 | Phones pull attention in class | Maths scores can go down |

| Higher Ed | Phones used for texts and email in class | Focus drops and grades can suffer |

How Many Students Are Distracted?

Data from PISA 2022 aligns with earlier results. In schools with phone bans, about 29% still check phones several times a day, and about 21% do so daily or almost daily. About 59% report being distracted by nearby devices in maths lessons, and frequent pull links are associated with lower scores. Diary data from campuses shows the same pattern: fast checks during class and brief replies. Outside class time, tools that guide problem steps also appear more often. For example, geometry AI helps break down a proof or shape task into clear stages, and many learners rely on it to follow the logic after the lesson ends without extra cost or a private tutor. Typical phone actions in class:

- Reply to a short message

- Look at new posts on social apps

- Check email inbox for new information

- Tap an alert on the lock screen

- Open a calculator or homework tool

No single number fits all schools. Rules differ, follow-through differs, and subjects demand different levels of focus. Family and teacher views also vary between safety access and strong limits. Across sources, a steady range appears: about 20–30% use phones daily during the school day, and about one-half to three-fifths report attention pull from peer devices in a typical lesson.

What Teachers and Students Think About Cell Phone Use

Teachers talk bluntly about devices in the classroom. A majority of them assert that phones divert attention, slow down progress, and later on, show up as lower grades and less recall of the course material. Surveys confirm this view: more than half of the respondents characterize the effect as “very negative” and parents are almost equally close to them in opinion. A clear majority of U.S. adults support a ban on phones during class time.

Students answer with a less serious view. They admit to a quick check but maintain that they return to work quickly. This difference sets the gap: adults focus on the results, while students focus on the intentions. Schools can prioritize lesson plans as the main focus, have brief open periods for the use of handy tools, and demonstrate the responsible use of technology without every rule being a punishment. Thus, phones become tools for work rather than devices that lead the attention away, and responsible technology is a real thing, not just something printed in a handbook.

Policies, Bans, and What Actually Changes Behavior

Phone regulations in schools are becoming stricter worldwide. According to UNESCO, 79 education systems had imposed limits on student phone use by late-2024, which is almost 40% of the countries. In England, the movement for a ban is stronger at the school level: more than 90% of secondary schools and almost all primary schools have a phone restriction during the day. The change indicates how quickly leaders acknowledge the presence of phones as a normal part of the classroom, rather than a rare phenomenon, and thus, they react accordingly.

Prohibitions are beneficial only when employees are carrying them out. This is clear from OECD data. 29% of students in schools with rules still check their phones several times a day, and 21% use them daily or almost daily. Behavior only changes when there are lockers, pouches, or a storage place under the supervision of a staff member for phones, and not merely a line in a handbook with which the rules have been met. In the United States, regulations are district-dependent. Approximately three out of ten public schools have a policy of blocking phones during the whole school day or every class, while others allow use during breaks or a teacher’s signal.

Learning Outcomes and Behavior

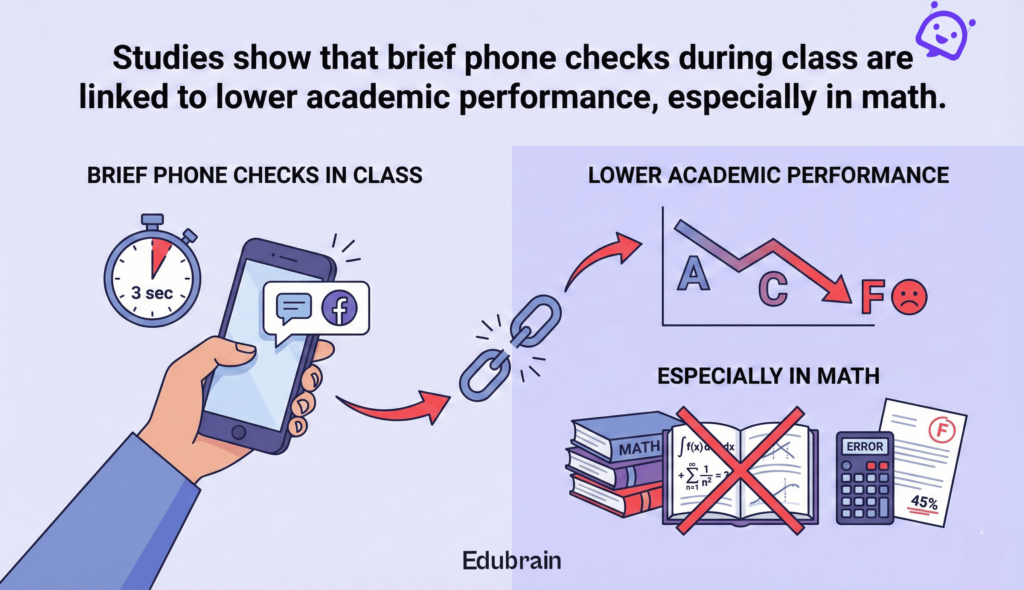

Most of the time, data points converge. If phones are not put on silent during the lessons, then concentration deteriorates and learning becomes less effective. Findings by the OECD show that frequent checks and feeling that one’s phone is buzzing, even when unaware, are linked to lower maths scores. Students who multitask between different screens and schoolwork are also less likely to recall and take more time to complete their tasks. Here are the core takeaways:

- Regular phone checks line up with weaker maths results

- Watching others use phones hurts focus too

- Limits link to more on-task behavior and smoother lessons

- Results improve most when staff follow through, not just write rules

Phones are not the only factor. Classroom routines, clear goals, strong instruction, and home life also play a role. Still, many studies point to one steady result: when a school treats the phone as a tool for specific moments instead of a constant companion in the pocket or on the desk, students hold their attention more easily. With fewer pulls away from the task, clearer thought fits into the same class time.

Why Students Go Off-Task

College diaries reveal that the main reasons for such straightforward behaviors are boredom, habit, and the myth that multitasking helps. Whenever there is a dull moment in a lecture, people quickly take out their phones and scroll. It is quite common for one ping to become three without you realizing it. After that, memory gets worse. However, the pattern changes when a teacher incorporates technology into their lesson, such as polls, shared notes, and quick research that leads to the next question. Thus, the device is used for the task instead of being a distraction. The same holds when guidance matches the moment. A class that explores study paths – say, majors that don’t involve math – can use phones to check requirements and bring answers back to the room. Key factors to watch:

- Open Wi-Fi and unmonitored time invite drift

- Clear norms, visible storage, and “tech-on/tech-off” cues cut noise

- Active learning keeps hands busy and heads in the room

- Short, timed phone windows reduce random checks

To put it shortly, it is the structure that is the deciding factor. When the strategy provides the tool with a sense of direction and the space with obvious rules, students concentrate. They become scattered if the internet is accessible for everyone without any restriction, the time is not controlled and the phone is the only thing that can be used for an interesting activity.

Practical Ways to Cut Distraction

Typically, a gradual program is more effective than an abrupt prohibition. Educational institutions achieve outcomes when they maintain elementary, consistent, and equitable standards of behavior. Regulations concerning the use of phones and other devices remain unchanged, whether they are in the corridor or the classroom, and parents receive the identical communication at home. Key moves that make a difference:

- Clear norms and follow-through: one set of rules across the school, same reminders, same consequences

- Phone-free blocks: short periods with no screens reduce divided attention and help brains reset

- Lockable pouches or storage spots: screens stay out of sight, not just “off”

- Active lesson design: cold calls, turn-and-talk, and quick checks keep eyes up and minds in the room

- Timed tasks on devices: goal set, timer on, share out – structure builds self-discipline and self-control

Timing matters too. With a quarter coming, short retrieval drills help memory stick and boost long-term retention. When routines feel fair and predictable, teenagers receive them well – and attention stays on the work, not the screen.

Conclusion

Phones will not disappear from school life, but the way they are handled matters. When the phone stays in a bag or pouch and comes out only at clear points, attention holds longer and lessons move with fewer breaks. A single set of rules across the school, clear reminders from adults, and a consistent message at home provide students with a fair structure. The goal is not to punish or remove every device, but to ensure the phone does not take center stage during the lesson. With the pull of the screen reduced, students think with more focus, finish more work in class, and feel less strain trying to keep up.

Explore Similar Topics

Teachers face constant pressure across lesson plans, assessments, differentiation, parent messages, and admin tasks. Smart AI tools can cut routine...

Are you a high school student curious about chemistry? Many summer programs are available to help you explore this exciting...